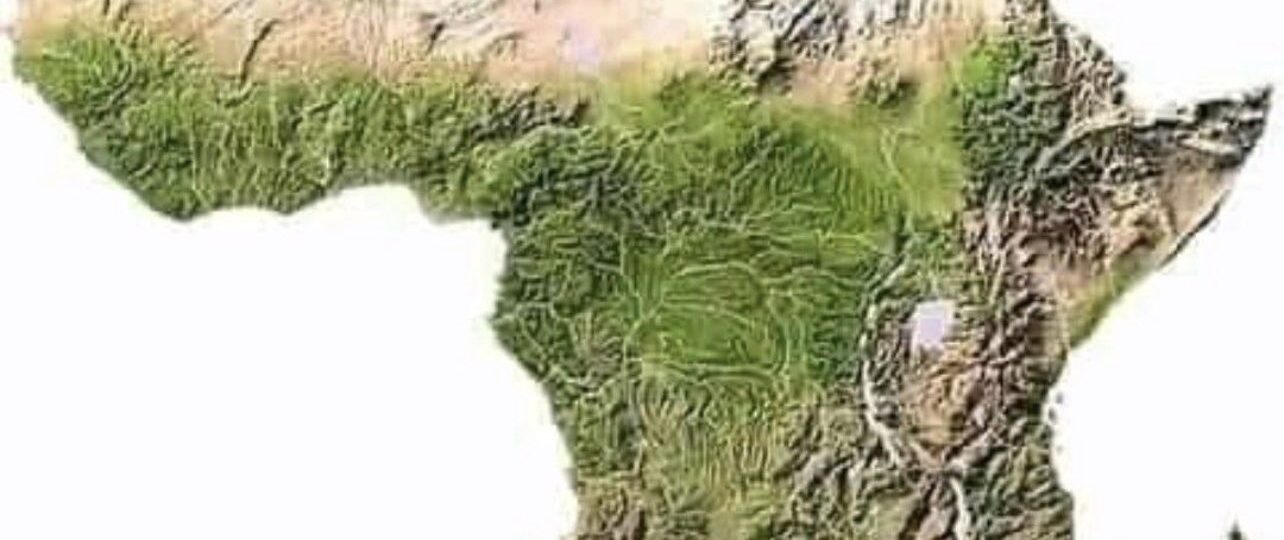

Africa is a vast and diverse continent – imagine a tapestry woven with deserts, rainforests, mountains, plateaus, and rivers. Have you ever wondered why North Africa seems so different from Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of population and settlement patterns? The secret lies in its geography. Physical features like deserts, mountains, and great rivers act as barriers or lifelines, shaping where people live, work, and build communities.

In this article, we’ll take you on a journey across Africa – from the Sahara and Sahel in the north to the Congo Rainforest, Ethiopian Highlands, Atlas Mountains, Kalahari Desert, Great Rift Valley, and the mighty Nile and Congo Rivers – to see how each feature influences settlement patterns. Each of these landscapes influences where and how people settle – acting like walls, corridors, oases, or magnets for life and commerce. We’ll explore historical examples, modern developments, challenges people face, and opportunities created by these landscapes. By the end, you’ll understand how Africa’s geography has drawn lines that humans have to adapt to or overcome.

The Sahara Desert

Imagine a colossal wall of sand, stretching from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. That’s the Sahara Desert – the world’s largest hot desert, covering about 9 million square kilometers (bigger than the U.S.!). Its climate is brutal: scorching days, freezing nights, and almost no rain. These extremes make it nearly uninhabitable except in a few green oases or mountain refuges. As a result, the Sahara has always been a natural barrier between Africa’s north and south. Cities and settlements cling to the edges – from Cairo in the northeast all the way to Timbuktu in the west – rather than being spread across the desert itself.

Historically, the Sahara’s vastness shaped how people moved and traded. For thousands of years, caravans of camels trudged along routes from Mediterranean ports deep into West Africa, carrying salt, gold, and ideas. The legendary trans-Saharan trade routes linked North African markets with powerful kingdoms like Mali, Ghana, and Songhai. But it was never easy: traders perished in sandstorms or died of thirst. These routes gave rise to oasis towns like Agadez (Niger), Timbuktu (Mali), and Ghardaïa (Algeria) – which became hubs of culture and commerce.

In modern times, the Sahara continues to influence settlement patterns and development. It remains sparsely populated – for example, the Libyan and Algerian Saharan regions have only a few million people amid vast emptiness. Infrastructure projects like the Trans-Sahara Highway attempt to stitch the continent together with roads, but these projects are slow and expensive. At the same time, discoveries of oil and minerals under the sands (in Algeria, Libya, and Niger) have led to new towns and economic hubs popping up on the desert fringes. However, people in those areas still contend with extreme heat and drought; southern edges of the Sahara are even moving northward as desertification pressures communities to relocate.

However, the Sahara is not just a barrier – it’s also a land of opportunity. Its wide-open spaces receive intense sunlight, ideal for massive solar-energy farms that could power cities hundreds of miles away. Adventure tourism (trekking, dune safaris, even movie filming) has boomed in Morocco and Tunisia’s deserts. Traditional knowledge – from ingenious well-digging to building cliff-carved villages – keeps communities alive in unexpected pockets. Despite its harshness, the Sahara shapes Africa’s settlement by forcing anyone who lives near it or crosses it to adapt, prepare, and innovate in unique ways.

The Sahel Region

Just south of the Sahara lies the Sahel – a semi-arid belt stretching from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east. It’s often described as a “transition zone” or a green fringe. The land here is drier than the savannah below but not as harsh as the Sahara. This means the Sahel can support grasses, shrubs, and some hardy crops, making it home to grazing pastoralists (herders moving livestock) and farming villages. But life here is precarious – rainfall is unpredictable, and the soil is prone to degradation.

Historically, the Sahel was once wetter and saw the rise of great medieval empires. Kingdoms like Ghana, Mali, and Songhai thrived on rain-fed agriculture and trade, and cities like Timbuktu and Gao were prosperous cultural centers. But over centuries, the climate dried. The famous droughts of the 20th century (like the 1970s Sahel drought) devastated harvests and forced people to move. Today, you might see villages abandoned where verdant fields once flourished, a stark sign of how fragile this middle ground is.

In modern Africa, the Sahel continues to shape where people live. Its towns and capitals (like Niamey in Niger or Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso) tend to cluster along the wetter southern edge or near rivers and wells. Nomadic groups like the Tuareg and Fulani have adapted by migrating seasonally between the Sahel and greener savannas. However, overuse of the land and climate change are big challenges. As farmland expands northward or as droughts hit, conflicts can flare between farmers and herders fighting over shrinking resources. Initiatives like the “Great Green Wall” project aim to plant trees and restore degraded land, creating new opportunities for agriculture and stabilizing settlements.

Nevertheless, life in the Sahel is one of resilience and innovation. People herd cattle, goats, and camels; they grow millet and sorghum; they trade in bustling markets. Traditional rainwater harvesting, drought-resistant crops, and international aid all help communities survive. In this way, the Sahel stands at a crossroads – shaped by both the desert to its north and the lush tropics to its south – influencing migration, culture, and settlement patterns in Africa’s heartland.

The Congo Rainforest and Basin

Running just south of the Equator in Central Africa, the Congo Basin contains the planet’s second-largest rainforest. From Cameroon in the west all the way east to Uganda and south to the Angola border, thick jungle blankets the land. This environment is humid, hot, and famously dense – rivers and patches of forest dominate, with wildlife like gorillas and forest elephants. For settlement, it means something opposite of the Sahara: the forest itself limits large cities. Instead, most people live near rivers and clearings by the water, while the deep jungle remains lightly inhabited.

Historically, Central Africa’s rainforest acted as its own kind of barrier and connector. It was a challenge for outside explorers – one reason European colonizers took longer to penetrate the interior. Yet along the mighty Congo River and its tributaries, kingdoms and communities thrived (like the Luba and Kongo kingdoms). Small villages dotted clearings where farming was possible. In some ways, the Congo plays the opposite role of a desert: instead of pushing people to the edges, it gathers them into river corridors, while keeping the interior relatively undeveloped.

In modern times, the Congo Rainforest still keeps population density relatively low. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is huge, but much of its center has few roads or electricity. Logging and mining towns appear where companies invest (like Lubumbashi in the south for copper, or Libreville in Gabon for timber), but otherwise the forest remains wild. Challenges like malaria, conflict, and lack of infrastructure mean villages and farms stay small and scattered. On the other hand, the Congo Basin provides unique opportunities. Its forests are famous for biodiversity and carbon storage. Efforts to build eco-lodges and preserve parks (like Virunga National Park) have shown how valuable these jungles can be. In a way, the rainforest means people and wildlife have carved out a living right at the edges – or survived deep inside – in ways that differ dramatically from dry deserts.

The Ethiopian Highlands

Now shift to eastern Africa. The Ethiopian Highlands, often called the “Roof of Africa,” cover much of Ethiopia and parts of Eritrea. These are high mountain and plateau regions – think elevated plains and rugged peaks (some over 4,500 meters). Because of altitude, the climate is cooler and receives more rain than the surrounding lowlands. This has made the highlands a natural home for dense human settlement. Cities like Addis Ababa (the Ethiopian capital) sit on this plateau. The highlands have rich soils from volcanic rock, so agriculture thrives here.

Historically, the Ethiopian Highlands fostered one of Africa’s oldest civilizations. Axum, Lalibela, and Gondar are remnants of powerful kingdoms and rock-hewn churches built among these mountains. People have terraced the slopes for farming for millennia. This high ground also provided natural defense; invaders coming from the Red Sea or lowlands had difficulty penetrating into the heartland, allowing Ethiopia to resist colonization longer than many neighbors. Even today, the Highlands are the demographic heart of Ethiopia: most Ethiopians live on these plateaus, which range in altitude but are all above 2,000 meters.

In modern times, the Ethiopian Highlands remain heavily populated and cultivated. Terraced fields of teff, barley, and coffee cover the hillsides. Towns and villages dot the ridges, with waterways running down to feed the Rift Valley lakes and the Nile Basin. Challenges here include soil erosion on steep slopes and occasional droughts, but overall the Highlands act as a breadbasket for Ethiopia. Opportunities also emerge: the highlands are ideal for hydroelectric dams on rivers (like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile) and for tourism to historic sites and great mountain views.

Overall, the Ethiopian Highlands show how elevation can concentrate population. Unlike the Sahara, which pushes people to the edges, these mountains pull people together. The result is a vibrant network of settlements that face their own problems (erosion, land pressure) but also benefit from fertile ground, abundant rain, and strategic advantage in the region.

The Atlas Mountains

In North Africa, the Atlas Mountains stretch across Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. These ranges rise over 4,000 meters (for example, Mount Toubkal in Morocco) and act as a barrier between the Mediterranean coast and the Sahara. North of the Atlas, the climate is Mediterranean (wet winters, dry summers); south of the Atlas, it’s arid and Saharan. This elevation divides Northern Africa from the interior.

Because of their height, the Atlas region gets more precipitation, allowing forests and agriculture on its slopes. Historic cities like Marrakech and Fes (in Morocco) sit near its foothills, and mountain valleys are home to traditional Berber villages. These mountains have been both obstacles and sanctuaries. For example, in Roman times and later, armies and traders had to find mountain passes to cross them. In modern times, the Atlas still dictates settlement: people live in the valleys and on cooler high plains, not in the dry lowlands.

Challenges in the Atlas include earthquakes (it’s tectonically active) and limited farmable land on steep slopes. But there are opportunities too: the mountains provide water for both North and West Africa (rivers like the Sebou and Chelif start there), and their scenery supports tourism (hiking, skiing, cultural tours). The Atlas Mountains showcase a climatic and cultural divide: north of the range, dense populations live in coastal plains and cities; south of it, settlements thin out into desert and Sahel zones.

The Kalahari Desert

Heading to southern Africa, we meet the Kalahari. It’s a semi-arid sandy plain covering Botswana, Namibia, and parts of South Africa and Angola. Unlike the lifeless Sahara, the Kalahari supports some vegetation and seasonal waterholes (hence “semi-arid”). Yet it’s still sparsely populated. The San (Bushmen) are among the traditional peoples here, living as hunter-gatherers for millennia. Modern settlement tends to cluster on the edges or around sources of water (like in the Okavango Delta to the north or smaller oases scattered in the sands).

The Kalahari has a subtler influence on settlement patterns. It’s not as big a barrier as the Sahara, but it does mark a change in the landscape: south of it lie the more fertile farmlands and cities of South Africa. The northern Kalahari is a tough zone for farming, so historically people mostly passed through it en route to coastal ports. In modern times, the Kalahari region is lightly populated with scattered ranches and villages. Botswana’s capital, Gaborone, sits at the southern edge of the Kalahari – not deep inside it.

Challenges in the Kalahari include chronic water scarcity and ongoing desertification. Opportunities include mining (Botswana is famous for its diamond mines hidden in Kalahari sands) and tourism (game reserves, wildlife safaris, and desert adventures). The Kalahari Desert illustrates how a semi-desert can still shape settlements: people cluster around the margins and the rare water sources, while the heart of the desert remains virtually empty.

The Great Rift Valley

Now for a north-south fault line: the Great Rift Valley. This massive trench runs from the Red Sea in the north through East Africa down to Mozambique – a kind of grand geological scar. In Africa, it creates a string of highlands, plateaus, and lakes. The East African Rift has deep valleys (up to 10 km deep in places) with huge lakes like Victoria, Tanganyika, and Malawi. Importantly, many Rift areas have volcanic soil that’s very fertile.

Because of the Rift’s geology, settlement along it is dense in spots. The Ethiopian Rift hosts Addis Ababa and fertile farming lands. The Kenyan Rift Valley is home to Nairobi and other cities on its high edges. The long lakes (like Lake Victoria and Lake Tanganyika) support fishing villages and intensive agriculture on their shores. Some flat areas of the Rift (like parts of the Serengeti in Tanzania) are famously wildlife-rich but sparsely settled by people.

Historically, the Rift is even known as the “Cradle of Humankind”: fossil finds in Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) and the Omo Valley (Ethiopia) show our ancestors lived here millions of years ago. Traveling through the Rift could be easier than crossing deserts, since game trails and lakes guided movement. The Rift also provided resources: salt from dried lake beds, and trade routes along the broad valley floors.

In modern East Africa, the Rift Valley is a backbone of infrastructure and settlement. Major roads and railways follow the flat valleys. Many Great Lakes cities (like Kampala on Lake Victoria, Kisumu on Lake Victoria, Mwanza, and Bukavu) grew up because of lake trade and agriculture. There are challenges: the region is tectonically active (earthquakes, volcanoes, e.g. Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya), and seasonal floods or droughts can impact the valley. But it offers big opportunities: extremely fertile land for farming, hydroelectric potential (like the dams on Lake Victoria outflows and projects on tributaries), and rich tourism (safaris in the Serengeti, climbing Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya). The Rift Valley shows how a giant crack in the earth can become a lifeline – attracting people, water, and culture along its length.

The Nile River

Flowing south to north, the Nile River is Africa’s iconic waterway. It has two main tributaries: the White Nile (starting in the Great Lakes region of East Africa) and the Blue Nile (from the Ethiopian Highlands). Wherever the Nile goes, life and settlements follow. Northern Africa’s largest city, Cairo, is on the Nile, and almost all of Egypt’s 100+ million people live along the Nile Valley or Delta. This isn’t surprising: the Nile provides water and fertile soil in an otherwise desert continent.

Historically, the Nile Valley was the cradle of ancient Egypt. The yearly floods deposited rich silt on its banks, allowing Egyptians to farm grain and build monuments like the pyramids. Cities like Thebes (Luxor) and Memphis grew along it. Farther south, the Nile linked cultures between Egypt and Nubia (in modern Sudan) and was a highway of transport. Even before modern roads, the Nile was one of the few “roads” through the arid landscape, so settlements and kingdoms clustered around its banks.

In modern times, the Nile still determines settlement patterns. The river’s irrigation and dams (like the Aswan High Dam) support agriculture that feeds millions. New towns rise on Nile banks, such as planned desert communities in Egypt’s Western Desert that rely on Nile water. However, conflicts over water are a challenge: the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has led to debate with downstream countries like Sudan and Egypt. Floods or droughts can create problems or trigger migrations. Without the Nile, Egypt and northern Sudan would be mostly barren.

The Nile River illustrates the north-south connection too: it literally brings waters from East Africa (Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia) into Egypt’s heart. Its role shows how a single river can bridge climates – tropical at its source, desert at its end – shaping settlement over thousands of years.

The Congo River

The Congo River drains much of Central Africa. It winds through the heart of the Congo Basin and is the second-largest river in the world by volume (after the Amazon). Unlike the Nile, the Congo cuts through dense rainforest, making navigation tricky in places due to rapids and waterfalls. Still, wherever the river runs, it supports population centers. The capital of the DRC, Kinshasa, is on one side of the river (with Brazzaville, capital of the Republic of Congo, on the other side), as are other major cities like Kisangani. Downstream, the river widens (for example around Pool Malebo) before it eventually empties into the Atlantic Ocean near the port of Muanda.

Historically, the Congo River was the lifeline of Central Africa. Before roads, African kingdoms (like the Kongo Kingdom and Luba Kingdom) and villages used it to move people and goods by canoe. European explorers (like Henry Morton Stanley) followed it deep into the continent. Cities sprouted at navigable points: for example, the area of Stanley Falls became Kisangani, and Brazzaville/Kinshasa grew where the river was first bridged. The river also separated and connected: its rapids mark limits of travel, which is why Kinshasa and Brazzaville are famous as “twin cities” separated by both colonial borders and river rapids.

In modern times, the Congo River remains crucial but underdeveloped. Large hydropower projects (like the planned Inga dams) are intended to harness its vast energy. Smaller towns and farms line parts of the river, but much of it still flows through sparsely-settled forest. Shipping still occurs where possible (boating upriver from the coast), but the rapids force goods to be carried overland around obstacles. Challenges include political instability in the region and pollution affecting river health. On the opportunity side, the river provides freshwater fish and acts as a transportation corridor into remote areas, offering huge hydro potential.

The Congo River shows how a great tropical river shapes settlement. Unlike northern deserts, it doesn’t create a simple north-south divide – instead, it carves an east-west route that draws people into Central Africa. Its basin is a unity in itself, and cities like Kinshasa, Mbandaka, and Kisangani exist because the Congo flows by them.

Challenges and Opportunities Across Africa’s Divide

Africa’s physical features that shape settlement also bring challenges and opportunities. On the challenge side, natural barriers and extremes mean:

- Transportation hurdles: Crossing vast deserts or thick forests requires huge investments. For example, only a few paved roads cross the Sahara or Congo, and remote communities often lack access to healthcare, markets, or schools.

- Climate pressures: Regions like the Sahel face drought and desertification, forcing migrations and food insecurity. Flooding in river deltas or soil erosion in mountains also threaten homes and farms. Seasonal climate swings can devastate harvests in vulnerable areas.

- Resource conflicts: Limited fertile land and water in contested zones can spark disputes. Water politics along the Nile or clashes between farmers and herders in the Sahel illustrate how geography can contribute to tension.

- Uneven development: North Africa (with its coasts and oases) and some southern cities (like Cape Town or Johannesburg) have advanced infrastructure, while central forests and deserts lag behind. This disparity reinforces a north-south economic and settlement gap.

However, geography also creates unique opportunities:

- Renewable energy: The intense sunlight of the Sahara and Kalahari is ideal for solar farms. Windy mountain passes in the Atlas and geothermal hotspots in the Rift offer green power. Projects like Morocco’s massive solar plant and Kenya’s geothermal fields showcase this potential.

- Rich resources: Many physical features hide valuable resources – oil under desert sands, minerals in highlands, timber and carbon in rainforests, fish in great rivers. Responsible extraction and trade of these can fund development.

- Tourism and culture: Spectacular landscapes attract visitors (Saharan dune adventures, Mount Kilimanjaro treks, Nile cruises, Serengeti wildlife safaris). Traditional lifestyles (nomadic herders, highland farmers) contribute cultural diversity that can also become tourism attractions or sources of local products (coffee, crafts).

- Strategic corridors: Rivers (Nile, Congo) and valley passages (Rift Valley) serve as trade and migration routes. Improved navigation or road-building can link communities (for instance, plans for transcontinental railways or highways). These corridors can help unify regions that geography otherwise isolates.

- Agricultural zones: The more hospitable regions (highlands, river valleys, some Sahel savannas) can become breadbaskets if managed well, helping feed growing populations and reducing north-south food disparities.

In summary, each physical feature has carved division lines in Africa – but it also stitches communities to those very lines, creating chances to innovate around them. Understanding these challenges and opportunities is key to addressing Africa’s north-south settlement patterns in a sustainable way.

The question “Which geographic feature divides Africa north and south?” doesn’t have a single answer – it has many. From the towering sands of the Sahara to the living jungles of the Congo, Africa’s landscape weaves a complex story. The Sahara Desert and Sahel form a great belt across the continent; the rainforests, mountains, and lakes carve out different zones; and the great rivers thread it all together.

What is clear is that Africa’s settlement patterns – where people live and how they move – are deeply influenced by these natural features. In many ways, the Sahara has been the biggest divider, often seen as the boundary between “North” and “Sub-Saharan” Africa. Yet even that great desert is joined by the transitions of the Sahel, the break of the Rift, and the nourishment of the Nile and Congo. Each feature has carved a line and shaped civilization on either side of it.

Understanding this geography helps explain history (why empires rose where they did), economics (which regions develop first), and current issues (like migration or resource disputes). It also points to solutions: building bridges over natural divides, planting forests to halt desert expansion, and tapping the energy of sun and water. In short, the very features that divide Africa can also connect and sustain it – if people learn to work with nature.

Africa’s north-south settlement divide is thus not just a line on a map but a mosaic of landscapes that humans must adapt to. By learning from each feature – the challenges it poses and the chances it offers – African nations can better plan where to live and thrive in the future.

FAQs

Q: What physical feature is often cited as dividing North and Sub-Saharan Africa?

A: The Sahara Desert is most commonly cited, as it creates a vast natural barrier across the continent. Its extreme climate means few people live in the middle, so populations concentrate on either side – North Africa along the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan African regions like the Sahel or forest zones. However, it’s important to note the Sahara works with other features (Sahel, mountains) to create this divide.

Q: How have people adapted their settlements to the Sahara and Sahel regions?

A: In the Sahara, settlements are scarce and often located in oases or along the desert’s edges where water exists (like the Nile Valley or North African coast). People have built underground canals (qanats), dug wells, and developed nomadic herding lifestyles to cope with scarcity. In the Sahel, communities practice seasonal farming and herding; they plant drought-resistant crops and migrate between wet and dry areas. Projects like the “Great Green Wall” also aim to make the Sahel more livable by stopping desert spread.

Q: What role does the Congo Rainforest play in population distribution?

A: The Congo Rainforest’s dense jungle and poor soils mean it’s one of the least populated parts of Africa. People who do live there tend to settle along rivers and clearings where farming is possible. Cities in the Democratic Republic of Congo and neighboring countries often sit on the forest’s edges or along the Congo River. So, the rainforest concentrates settlement to its borders and river corridors rather than spreading communities throughout the jungle.

Q: Why do many major cities in Africa lie along rivers or coasts?

A: Rivers and coasts provide water, food resources, transportation, and trade routes. For example, the Nile allows agriculture in the desert, which led to cities like Cairo and Khartoum. The Congo River and Great Lakes support cities like Kinshasa and Kampala. Coastal access (like Cape Town or Lagos) supports fishing and global trade. In a continent where interior travel can be hard, being on a river or coast connects people to trade and reliable resources.

Q: How do Africa’s mountains create both challenges and opportunities for settlement?

A: Mountain ranges like the Atlas or Ethiopian Highlands make travel and farming difficult on steep slopes. This can isolate communities (a challenge). However, they also bring cooler climates and higher rainfall, creating fertile areas for agriculture (an opportunity). For example, the Ethiopian Highlands have a large population and successful coffee farming. Mountains can provide minerals, water sources (from snowmelt or springs), and tourism sites. So people often cluster in mountain valleys where life is easier and beneficial.