When you think of ancient North Africa, what image comes to mind? Perhaps pyramids rising from desert sands, or the bustling streets of ancient Carthage or Alexandria. But what about the people? Who truly were the indigenous populations of North Africa and the vast Sahara?

For too long, a distorted narrative has dominated the history of Africa—one that seeks to confine black Africans to regions south of the Sahara while erasing their ancient presence in North Africa. The term “Sub-Saharan Africa,” often thrown around in academic and popular discourse, is not a neutral geographical label.

It’s a colonial invention, a tool crafted in the 19th century to disconnect North Africa and ancient Egypt from the rest of the continent, using race as a dividing line. But the truth, rooted in historical accounts, archaeological evidence, and the lived experiences of indigenous peoples, tells a different story: black Africans have always been an integral part of North Africa and the Sahara, long before colonial powers rewrote history to suit their agendas.

Let’s start with the Sahara itself. Today, we picture it as an endless stretch of arid desert, a natural barrier separating “black Africa” from the north. But this image is a modern one. Around 7000 BCE, the Sahara was a lush, tropical paradise—a “Green Sahara”—teeming with rivers, lakes, and savannas.

It was home to thriving black African populations who lived, farmed, and herded cattle in this fertile landscape. Two prominent groups from this era, the Kiffians and the Tenerians, left their mark in what is now Niger. Archaeologists, like Paul Sereno, uncovered their remains at sites like Gobero, revealing the Sahara’s largest ancient cemetery.

The Kiffians, often described by early researchers as having a “Bantu phenotype,” were unmistakably African, while the Tenerians, with slightly different physical traits, puzzled some scholars who tried to label them as Eurasian. But their cultural practices, from cattle iconography to deity worship, mirror those found in later African civilizations like Nubia and Kemet (ancient Egypt), showing a clear continuum of black African presence across the region.

Historical records from antiquity further dismantle the myth of a racially divided Africa. In the 6th century, the Roman poet Corippus described the Berbers—indigenous North Africans—as “facies nigroque colorus,” which translates to “faces of the black colour.”

Around the same time, the historian Procopius contrasted the Germanic Vandals, who had settled in North Africa, with the Moors (or Maurusioi), noting that the Vandals were not “black-skinned like the Maurusioi.” These accounts, written long before the colonial era, confirm that the original inhabitants of North Africa were dark-skinned peoples, often indistinguishable from their neighbors further south.

Take the Toubou people, for example, a group whose history stretches back millennia. Herodotus, the Greek historian, visited the Libyan east coast around 450 BC and described the Toubou as “Ethiopian” or Abyssinian, locating them across a vast region from modern-day Fezzan in Libya to Chad, Niger, Sudan, and Central Africa.

The Toubou’s own oral traditions, as shared by their leader Sultan Zulai Mina Saleh, affirm their African identity: “We are the people of Africa. We are all black, but our features are different.” Archaeological evidence supports this, showing that the Toubou were among the first to settle in the Green Sahara, adapting to its desertification over thousands of years. Genetic studies, like one from 2019 by B. Lorente-Galdos, reveal that while the Toubou have some Western Eurasian ancestry (around 31.4%), their African roots are dominant, closely tied to other Sub-Saharan populations.

The cultural connections are just as compelling. The Green Sahara’s inhabitants migrated over time to regions like Napta Playa and the Nile Valley, bringing with them practices that would shape the foundations of ancient African civilizations.

The cattle iconography and deity worship—like the cow-headed goddess Het-Heru—seen in Kemet first appeared in the Sahara centuries earlier. Places like Qustul, Napata, and Waset (Thebes) became seats of Pharaonic kingship, led by black Africans whose legacy colonial scholars later tried to erase by inventing racial categories like “Sub-Saharan.”

Even the history of North Africa’s later inhabitants shows the deep African roots of the region. The Berbers, often portrayed as a non-black population in modern narratives, were described as black by ancient writers. The Masmuda, a Berber group who served as soldiers in the Fatimid dynasty, were called “black Africans” by the 11th-century Iranian writer Nasr Khusrau.

And during the 23rd and 24th Dynasties of Kemet (880–734 BC), Libyan kings of the Meshwesh tribe ruled Lower Egypt, a testament to the intertwined histories of North African and Nile Valley peoples. One such ruler, Iuput II, eventually submitted to the Kushite king Piye, who defended Kemet against foreign invaders around 728 BC.

So why the persistent myth of a non-black North Africa? It comes down to colonial agendas and the pseudoscience of race that dominated European scholarship in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The term “Sub-Saharan Africa” was weaponized to relegate black Africans to the south, while North Africa was reframed as a region tied to the Mediterranean and Eurasian worlds.

Theories like the Hamitic hypothesis—a racist idea that attributed African achievements to a supposed non-black “Hamitic” race—further distorted the truth. But the evidence, from ancient texts to modern genetics, tells a different story: black Africans are indigenous to the entire continent, including North Africa and the Sahara.

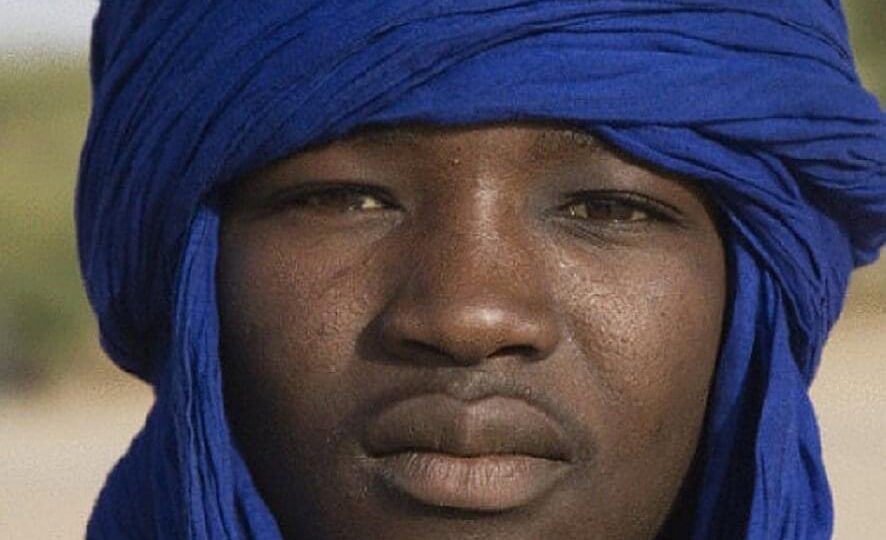

The images often associated with these discussions—photographs of people adorned in intricate jewelry, draped in vibrant fabrics, and wearing headdresses that reflect centuries of tradition—remind us of the living cultures that continue to thrive in these regions. The Tuareg, the Berbers, the Toubou—all are part of a rich tapestry that defies colonial attempts to divide Africa along racial lines. Their history, their resilience, and their very existence challenge us to rethink what we’ve been taught about the continent.

It’s time to let go of the colonial myths and embrace a more honest understanding of Africa’s past. North Africa and the Sahara were never a barrier—they were a cradle for black African civilizations that shaped the continent’s history. From the Green Sahara to the Nile Valley, from the Toubou to the Meshwesh, the story of Africa is one of unity, diversity, and enduring legacy. Let’s honor that truth by rejecting the labels and divisions that were imposed upon it.

Sources:

Oyeniyi, Bukola Adeyemi. The History of Libya. Greenwood, 2019.

Corippus, Johannis, 6th century.

Procopius, History of the Wars, Book IV, 6th century.

Herodotus, The Histories, 450 BC.

Lorente-Galdos, B., et al. (2019). Whole-genome analysis of Sub-Saharan populations.

Sereno, P., et al. Excavations at Gobero, Niger.