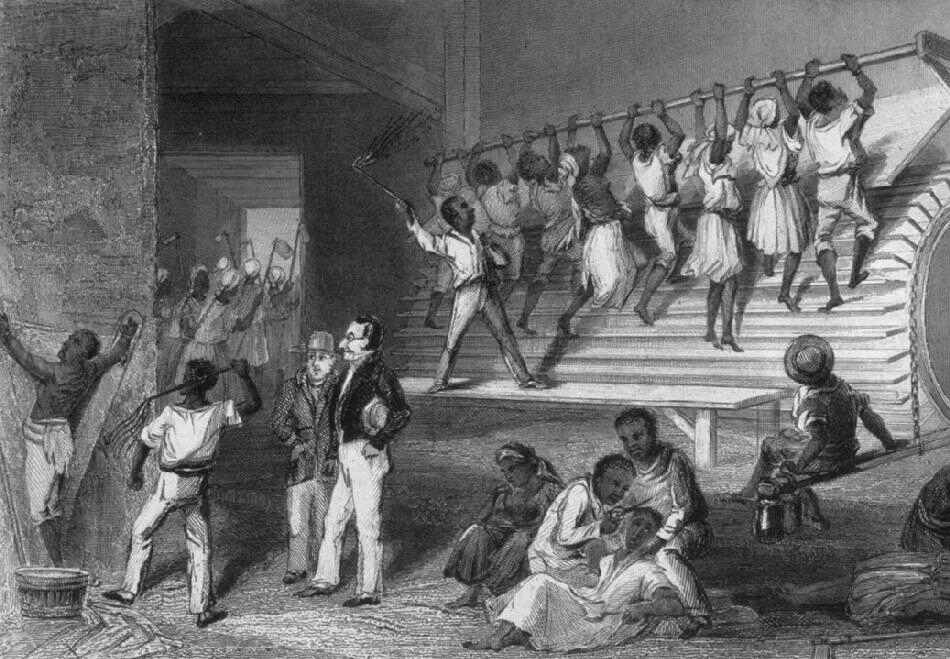

The Transatlantic Slave Trade represents one of the darkest chapters in human history, forcibly uprooting millions of Africans from their homelands and scattering them across the Americas. While the collective narrative often speaks of a monolithic “African diaspora,” beneath this broad umbrella lies a mosaic of distinct ethnic groups, each with their own unique cultures, languages, and spiritual traditions.

Among these, the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria stand out, not only for their significant numbers in the forced migration but also for the tenacious, yet often unacknowledged, imprints they left on the cultures and societies of the Caribbean.

For centuries, the story of the lost Igbo diaspora has been whispered in folklore, discerned in linguistic echoes, and hinted at in spiritual practices, but rarely fully articulated or widely recognized. This article delves deep into the profound, often submerged, Igbo heritage that persists in Jamaica, Haiti, Trinidad, Cuba, and other islands, exploring the historical evidence, cultural manifestations, and the ongoing efforts to reconnect these distant branches of the Igbo family tree. It’s a story of resilience, resistance, and the enduring power of cultural memory against overwhelming odds.

1. The Historical Underpinnings: The Bight of Biafra and the Forced Voyage

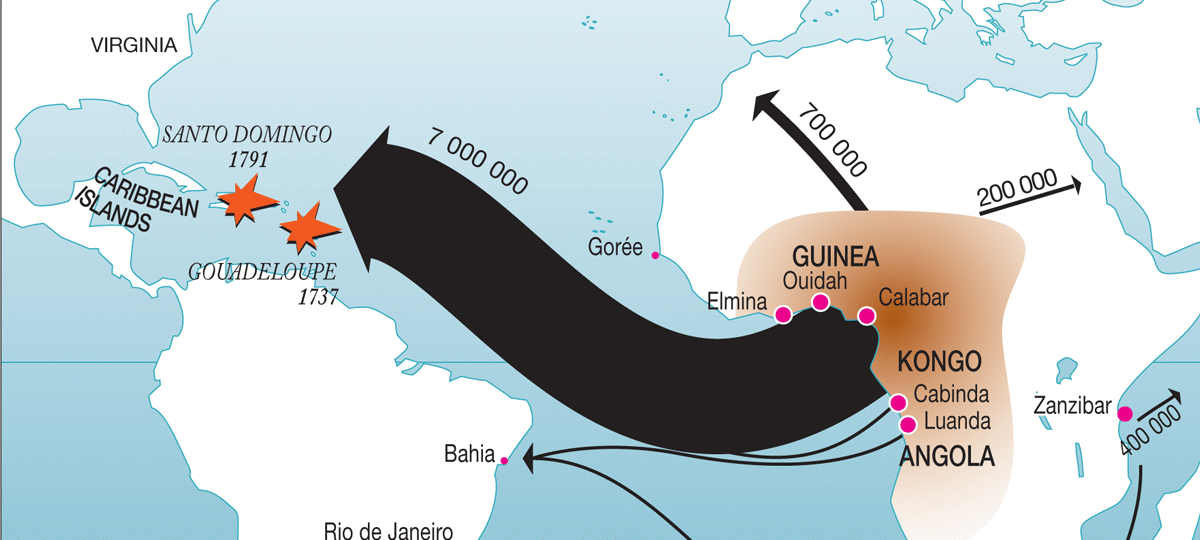

To understand the Igbo diaspora in the Caribbean, one must first grasp the scale and mechanics of the Transatlantic Slave Trade from the Bight of Biafra. While many African regions contributed to the slave trade, the Bight of Biafra, encompassing the coastal areas and hinterlands of what is now southeastern Nigeria, became one of the most prolific sources of enslaved people, particularly in the latter half of the 18th century. Ports like Bonny and Calabar (though primarily Efik, they funneled many Igbo captives from the interior) saw hundreds of thousands of individuals, predominantly Igbo, forcibly loaded onto slave ships bound for the Americas.

Estimates vary, but historical records suggest that anywhere from 1.5 to 2 million people were taken from the Bight of Biafra between the 17th and 19th centuries, making it a critical source region second only to West Central Africa (Angola/Congo). Of these, a significant proportion, possibly over 60%, were Igbo. This massive demographic outflow meant that Igbo people were not just present in the Americas, but often constituted a numerical majority among enslaved African populations in specific regions of the Caribbean.

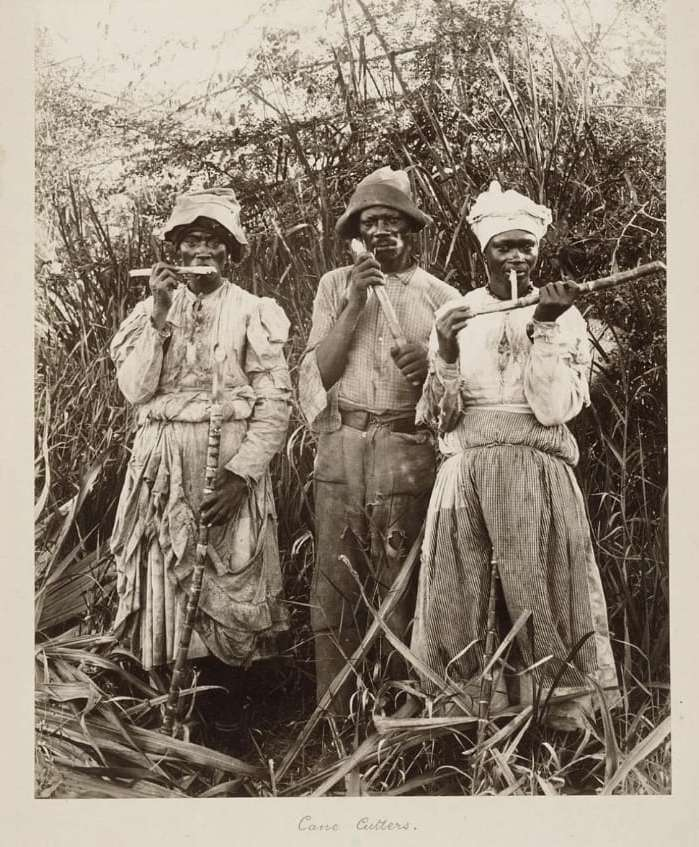

European slavers and plantation owners often categorized enslaved Africans by their perceived “nations” or “tribes.” In plantation inventories, baptismal records, and other colonial documents across the Caribbean, terms like “Eboe,” “Ibo,” “Calabar,” and “Biafran” frequently appear, denoting individuals of Igbo origin. These designations, while sometimes broadly applied, served to acknowledge a distinct ethnic identity among the enslaved, an identity that brought with it specific cultural traits, skills, and, crucially, a reputation for being fiercely independent and rebellious.

The journey across the Middle Passage was a brutal crucible designed to strip away identity and humanity. Yet, even in this horrific environment, cultural markers persisted. The concentration of Igbo people on particular ships or in specific Caribbean colonies meant that, despite deliberate attempts at mixing ethnic groups to prevent rebellion, a critical mass of Igbo language speakers and cultural practitioners often arrived together, facilitating the retention and adaptation of their heritage. This demographic concentration was a crucial factor in the survival of Igbo heritage in a way that might not have been possible for smaller, more dispersed groups.

2. Echoes in Language: Lingering Lexicons and Grammatical Structures

Language is perhaps the most fragile, yet most telling, indicator of a lost heritage. In the context of slavery, African languages were deliberately suppressed, as slave owners sought to eradicate any common ground that could facilitate rebellion or maintain cultural cohesion. Despite this, remarkable linguistic remnants of Igbo have survived in the creole languages of the Caribbean, particularly in patois, Papiamento, and Haitian Creole.

While no full-fledged Igbo language survived the generations of slavery, its lexical and structural influences are discernible:

- Loanwords: Numerous words in Caribbean creoles have identifiable Igbo origins.

- “Yam” and “Okra/Okro”: These are perhaps the most universally recognized African loanwords in the Caribbean, and while their origins can be broadly West African, the prominence of yam cultivation and consumption in Igboland (where it is often seen as the king of crops) points to a strong Igbo connection. The word “yam” itself is often linked to the Igbo word nyama or anyam.

- “Obeah”: This term, widely used across the Caribbean to refer to a system of folk magic, spiritual practices, and sometimes sorcery, has strong Igbo etymological roots. It is believed to derive from the Igbo word obi (heart, spirit, mind) or dibia (a traditional healer, diviner, or sorcerer). The practice of obeah, with its focus on spiritual power and ancestral communication, bears a striking resemblance to traditional Igbo spiritual beliefs and practices.

- “Akwaba” or “Accompong”: In Jamaica, the Maroon town of Accompong is named after a Maroon leader. While its direct Igbo origin is debated, it resonates with the Akan word nkɔmpɔn (wise man) or the Igbo expression aka mpon (strong hand/leader).

- “Afufu” or “Fufu”: While fufu is a staple across West and Central Africa, its name in some Caribbean contexts resonates directly with Igbo fufu, a fermented cassava dough.

- Other Potential Words: Scholars have identified other potential Igbo loanwords such as “nkita” (dog), “nwa” (child), “dibia” (healer/doctor), and “oji” (kola nut), though their prevalence varies by island.

- Grammatical Structures and Phonology: More subtly, some Caribbean creoles exhibit grammatical features that align with structures common in West African languages, including Igbo.

- Serial Verb Constructions: This is a hallmark of many West African languages, where multiple verbs are strung together to express a single action or a sequence of actions (e.g., “He take the money run” instead of “He took the money and ran”). While not exclusive to Igbo, its prevalence in the creoles of regions with a high Igbo population suggests an influence.

- Tonal Influences: Igbo is a tonal language, where the meaning of a word can change based on the pitch of its pronunciation. While Caribbean creoles are not fully tonal, some phonological features and intonational patterns may subtly reflect the tonal heritage of their African roots.

- Proverbs and Oral Traditions: Beyond specific words, the very structure of thought and expression in proverbs, riddles, and storytelling found in the Caribbean often mirrors the rich oral traditions of Igboland, emphasizing wisdom, community values, and the power of narrative. For instance, the emphasis on communal responsibility and the wisdom of elders found in many Caribbean proverbs resonates deeply with Igbo traditional thought.

The linguistic traces, though fragmented, serve as powerful reminders that the enslaved Africans did not arrive as a blank slate. They brought with them rich linguistic heritages that, even under extreme duress, left indelible marks on the evolving languages of their new, harsh homes.

3. Spiritual Survival: Faith, Resistance, and Syncretism

Perhaps nowhere is the Igbo heritage more profoundly evident than in the spiritual and religious practices of the Caribbean. Forced conversion to Christianity was a key strategy of slave owners to control the minds and spirits of the enslaved. However, African religious cosmologies proved remarkably resilient, often persisting clandestinely or blending with Christian elements to form new, syncretic faiths.

The traditional Igbo worldview is deeply spiritual, centered around a supreme being (Chukwu), numerous lesser deities and spirits (Alusi), and a profound reverence for ancestors (Ndi Ichie). Concepts like chi (personal destiny/guardian spirit), reincarnation (ino uwa), and the interconnectedness of the living and the dead are central. These beliefs found fertile ground for adaptation and survival in the Caribbean:

- Haitian Vodou: While Vodou is a complex syncretic religion drawing heavily from various West African traditions (Fon, Yoruba, Kongo), scholars and practitioners often point to significant Igbo contributions. The Nago, a group often associated with Yoruba, sometimes also included Igbo. Concepts of ancestral veneration, spirit possession, and the pantheon of Lwa (spirits) resonate with Igbo spiritual practices. The persistent emphasis on the communal and the importance of spiritual connection to the land and ancestors finds echoes in Igbo traditional religion. Some Vodou drums and rhythms also share similarities with Igbo musical traditions.

- Jamaican Kumina: Kumina is an Afro-Jamaican folk religion and drumming tradition, primarily practiced in the parish of St. Thomas, an area historically known for its high concentration of Igbo slaves. Kumina worship involves drumming, dancing, and spirit possession, often by ancestor spirits (Zombies) or nature spirits (Myal). The language used in Kumina rituals is a distinct creole with strong African retentions, and linguistic analysis suggests a significant influence from Igbo, alongside Kongo and other West African languages. The spiritual hierarchy and the role of the “King” and “Queen” in Kumina ceremonies resonate with traditional Igbo social and political structures. The veneration of ancestors and the belief in their active involvement in the lives of the living are central to both Kumina and traditional Igbo spirituality.

- Obeah and Myalism: These systems of folk magic and spiritual healing, prevalent across the Caribbean, draw heavily from various African traditions, but their etymology and many of their practices point directly to Igbo roots. Obeah, as discussed earlier, links to the Igbo dibia (healer/diviner). Myalism, often seen as a counterpoint to Obeah, focused on healing, purification, and community well-being, and also carries significant African retention, including elements that can be traced to various West African traditions, including Igbo.

- Orisha Worship in Trinidad: While predominantly Yoruba in origin, Orisha worship in Trinidad likely absorbed elements from other West African groups present on the island, including the Igbo. The general West African cosmic view, with its emphasis on a hierarchy of deities and the importance of ritual, would have been familiar to Igbo adherents and could have easily integrated into emerging syncretic practices.

The survival of these spiritual practices was not merely a matter of cultural preservation; it was a profound act of resistance. By maintaining their connection to African spiritual worlds, the enslaved found solace, agency, and a powerful source of communal identity that transcended the brutal realities of their existence. These spiritual traditions became clandestine schools for cultural transmission, ensuring that the Igbo heritage (among others) lived on, often hidden in plain sight.

4. Cultural Vibrations: Music, Dance, and Daily Life

Beyond language and religion, Igbo heritage permeated the daily lives, artistic expressions, and social structures of enslaved communities in the Caribbean.

- Music and Dance: The lively, rhythmic, and often communal nature of Igbo music and dance found fertile ground in the Caribbean.

- Drumming Traditions: Igbo traditional music relies heavily on various forms of drumming (e.g., udu, ekwe, ogene). While specific Igbo drums may not have been replicated, the rhythms, call-and-response patterns, and the function of drumming in ceremonies and social gatherings continued in Caribbean forms like Junkanoo, Rara, and various drumming circles. The emphasis on polyrhythms and complex percussive layers is a shared trait.

- Masked Performances: While not exclusively Igbo, the tradition of masked performances (like the Mmanwu tradition in Igboland) for spiritual rituals or celebrations finds parallels in Caribbean carnival traditions and some folk performances.

- Storytelling and Folksongs: Many Caribbean folk songs and stories carry themes and structures reminiscent of West African oral traditions, including those of the Igbo. Songs of resistance, lament, and celebration, often with call-and-response elements, served as vital tools for cultural preservation.

- Foodways: The agricultural practices and staple foods of Igboland found their way to the Caribbean, shaping the culinary landscape.

- Yam: As mentioned, yam was a primary staple crop in Igboland, holding significant cultural and ritual importance. Its successful transplantation and continued cultivation in the Caribbean was due in large part to the knowledge and practices brought by enslaved Igbo people.

- Cocoyam (Taro/Dasheen): Another significant crop in Igboland, cocoyam also became a staple in the Caribbean, further demonstrating the transfer of agricultural knowledge.

- Fufu: The preparation of starchy staples like cassava and plantains into a pounded dough (fufu or variations like fou-fou) is a direct culinary link to West Africa, including Igboland.

- Naming Conventions: The practice of giving “day names” (names corresponding to the day of the week a child was born, like Monday, Tuesday, etc.) or “soul names” was common in some West African cultures, including parts of Igboland. While less direct than Akan day names, some Caribbean communities, particularly in Jamaica, had similar practices, and the prevalence of personal names beginning with “Nwa-” (meaning child of, a common Igbo prefix) further suggests an Igbo presence.

- Social Structures and Proverbs: The Igbo emphasis on communal living, democratic decision-making (though not in the modern sense, but via consensus and dialogue in lineage groups), and a strong work ethic, might have subtly influenced the formation of maroon communities and other forms of resistance or communal living. Proverbs and moral sayings often convey wisdom that resonates with Igbo philosophical traditions.

- The Legend of Igbo Landing: No discussion of Igbo heritage in the Caribbean would be complete without mentioning the powerful legend of Igbo Landing. While different versions exist across the Caribbean (most famously in St. Helena Island, South Carolina, but also with echoes in Jamaica), the core narrative recounts a group of newly arrived Igbo slaves who, rather than submit to bondage, walked collectively into the sea, choosing death over slavery, believing their spirits would return to Africa. This legend, whether a precise historical event or a powerful symbolic narrative, speaks volumes about the indomitable spirit of the Igbo people and their profound attachment to freedom. It served as an inspiration for generations of enslaved Africans and remains a potent symbol of resistance and the assertion of human dignity.

5. Island by Island: Specific Traces and Concentrations

While the Igbo diaspora spread across the entire Caribbean, some islands received particularly large concentrations of Igbo people, leading to more pronounced and identifiable cultural retentions.

5.1. Jamaica: The “Red Ibo” and the Kumina Connection

Jamaica received one of the largest contingents of enslaved Africans, and among them, Igbo people were remarkably numerous. Historical records often identify the “Eboe” or “Ibo” as a distinct and often rebellious group.

- Demographic Prominence: In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Igbo people constituted a significant portion, sometimes even a majority, of the enslaved population in certain parishes of Jamaica, particularly St. Thomas and Portland. This concentration allowed for greater cultural continuity.

- “Red Ibo”: The term “Red Ibo” or “Red Eboe” was commonly used in Jamaica to refer to Igbo people, possibly due to their lighter skin complexion compared to some other West African groups, or perhaps a reference to the reddish soil common in Igboland, or even the practice of using camwood (red dye) for body adornment. This racial descriptor, used by both colonial authorities and other enslaved Africans, highlights their distinct recognition.

- Kumina: As previously discussed, Kumina, concentrated in St. Thomas, is perhaps the most direct and vibrant link to Igbo heritage in Jamaica. Its spiritual practices, drumming, and particularly its unique creolized language, bear strong linguistic and cultural resemblances to Igbo. Scholars have meticulously documented the parallels, making Kumina a living testament to the enduring presence of Igbo traditions.

- Maroon Communities: The Maroon communities of Jamaica, composed of runaway slaves who established independent settlements, were melting pots of various African ethnicities. While many different groups contributed, the presence of Igbo individuals within these communities meant that elements of their culture, particularly their fierce independence and military strategies, may have also influenced Maroon societies. The legend of Igbo Landing is also linked to Jamaican folklore, albeit with variations.

5.2. Haiti: Vodou’s Igbo Thread

Haiti, the first independent black republic, has a rich and complex African heritage, with enslaved people arriving from diverse regions, including the Bight of Biafra. While the Fon and Yoruba influences on Haitian Vodou are well-documented, the Igbo heritage forms a subtle but significant thread.

- Nago and Igbo: The term “Nago” in Haitian Vodou often refers to a broad group of people from the Bight of Benin and beyond, including Yoruba, but scholars suggest it could also encompass Igbo people due to their shared geographical proximity and cultural interaction in Africa.

- Spiritual Parallels: The emphasis on ancestor veneration, the concept of a spiritual hierarchy, and the importance of communal rites in Vodou resonate strongly with traditional Igbo spiritual practices. The Lwa (spirits) associated with earth, fertility, and justice could find parallels in Igbo Alusi.

- Rebelliousness: Like in Jamaica, enslaved Igbo people in Haiti were known for their rebellious spirit. Their participation in the Haitian Revolution, often fueled by spiritual beliefs and a desire for freedom reminiscent of the Igbo Landing narrative, would have been significant. Accounts from the revolution often mention the diverse African origins of the fighters, and it’s highly probable that Igbo individuals played a role in the uprisings that led to Haiti’s independence.

5.3. Trinidad and Tobago: Carnival and Orisha Resilience

Trinidad and Tobago also received a substantial number of enslaved Africans from the Bight of Biafra, especially in the later period of the slave trade.

- Orisha Traditions: While Orisha worship in Trinidad is predominantly Yoruba-derived, the general West African cosmology and the emphasis on drums, dance, and spirit possession would have been familiar to Igbo adherents and could have facilitated the integration or coexistence of Igbo spiritual ideas within the broader African retentions.

- Carnival: Trinidad’s world-renowned Carnival, with its vibrant masquerade, music, and dance, has deep African roots. While a pan-African celebration, elements of performance, communal participation, and masked figures might subtly echo various West African traditions, including those of the Igbo. The “Kalinda” (stick-fighting) tradition, for example, has parallels with various West African martial and performance arts.

5.4. Other Caribbean Islands: Dispersed but Present

Igbo heritage can also be traced, albeit more faintly, in other Caribbean islands:

- Cuba: While Cuban Santería has strong Yoruba and Kongo roots, the broader “Arará” or “Carabalí” (a term often used for people from the Calabar region, hence encompassing Igbo) populations contributed to Cuba’s rich Afro-Cuban culture.

- Barbados and St. Vincent: Historical records indicate the presence of “Ibo” slaves on these islands. While specific cultural retentions might be less pronounced than in Jamaica or Haiti, the foundational presence suggests potential, albeit submerged, influences.

- Grenada: The “Eboe” presence in Grenada, particularly during the Fédon’s Rebellion in 1795, highlights their continued reputation for resistance.

The varying degrees of Igbo heritage retention across the Caribbean often correlate with the numerical concentration of Igbo people in specific areas, the intensity of their resistance, and the specific colonial policies towards enslaved populations.

6. The Veil of Amnesia: Challenges in Tracing Heritage

Despite the compelling evidence, the Igbo heritage in the Caribbean has largely remained “lost” or unacknowledged for centuries. Several factors contribute to this historical amnesia:

- Deliberate Suppression: Slave owners actively worked to dismantle African identities, languages, and religions, viewing them as threats to their control. Punishments for speaking African languages or practicing traditional religions were severe.

- Forced Mixing of Ethnicities: While some areas saw high concentrations of Igbo, plantation owners often deliberately mixed ethnic groups on the same plantation or ship to prevent communication and collective rebellion. This made it harder for specific ethnic identities to survive intact over generations.

- Lack of Written Records from the Enslaved: The vast majority of historical documents are from the perspective of the enslavers, who often used broad, imprecise, or pejorative terms for African groups. The enslaved themselves left few written records, making it challenging to trace individual or group histories.

- Oral Tradition Fragility: While incredibly resilient, oral traditions can become fragmented or syncretized over generations, especially when facing systemic pressures to conform to a dominant culture.

- Syncretism Obscuring Origins: The blending of African and Christian elements, while a brilliant survival strategy, often masked the original African components, making it difficult for later generations to discern the specific ethnic roots of their practices.

- Post-Emancipation Dynamics: After emancipation, there was often a societal push to shed “African” identities in favor of assimilation into European-defined norms, further obscuring the distinct ethnic origins of Caribbean peoples. The stigma associated with “African” practices also contributed to their suppression or re-contextualization.

- Focus on Dominant Narratives: Academic and popular discourse often focused on the most visibly dominant African groups (e.g., Yoruba or Kongo in specific contexts), sometimes overlooking the profound contributions of other significant populations like the Igbo.

These challenges underscore why the Igbo diaspora has remained “lost” for so long, requiring painstaking research and a willingness to look beyond conventional narratives to uncover its traces.

7. Rekindling the Flame: Modern Efforts and Discoveries

In recent decades, a growing movement of historians, linguists, anthropologists, and most importantly, diaspora communities themselves, are actively working to rekindle the flame of Igbo heritage in the Caribbean.

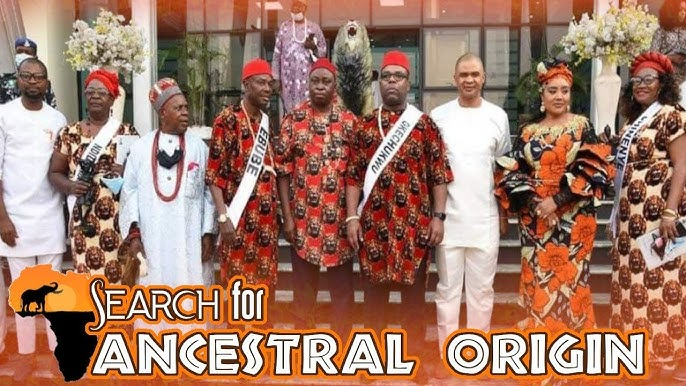

- DNA Ancestry Testing: The advent of affordable DNA ancestry testing has revolutionized diaspora studies. Many Caribbean individuals, previously unaware of their specific African origins, are now discovering significant Igbo genetic markers. This personal discovery often sparks a profound desire to learn more about their newfound heritage, driving interest in cultural exchange and historical research. These tests provide empirical confirmation for the historical records and cultural retentions.

- Academic Research: Scholars continue to delve into colonial archives, analyze linguistic patterns, and conduct ethnographic studies to unearth and document the Igbo heritage. Researchers like Maureen Warner-Lewis (on Jamaica‘s Kumina and Igbo linguistic influences) and others have made significant contributions, providing the empirical backbone for this reawakening. Their work helps to dismantle the generalized “African” label and highlight specific ethnic contributions.

- Cultural Exchange Programs: Increasingly, cultural organizations, universities, and individuals from Igboland are initiating direct exchanges with Caribbean communities. These programs involve visits, workshops, performances, and dialogues aimed at fostering mutual understanding and cultural reconnection. Imagine Igbo traditional dancers meeting Kumina practitioners, or linguists comparing proverbs – these interactions are powerful bridges across centuries of separation. For example, some Nigerian organizations have facilitated return trips for descendants, or cultural festivals featuring both Igbo and Caribbean performances.

- Diaspora Consciousness: There is a growing pride and assertiveness within Caribbean communities in embracing their specific African roots. No longer content with a generic “African” identity, many are actively seeking to identify and celebrate their specific ancestral lineages, including the Igbo. This shift in consciousness is driving new research, creative expressions, and community building initiatives.

- Digitalization and Accessibility: The digitalization of historical archives and the proliferation of online platforms have made it easier for researchers and interested individuals to access historical records and connect with others engaged in similar quests. This global network is accelerating the rediscovery process.

The journey of the lost Igbo diaspora is far from over. It is an ongoing process of discovery, reconciliation, and reconnection. Each word identified, each spiritual practice understood, each DNA match confirmed, adds another brushstroke to the vibrant canvas of Igbo heritage in the Caribbean.

The Indomitable Spirit of a Heritage

The story of the lost Igbo diaspora in Jamaica, Haiti, and the wider Caribbean is a testament to the extraordinary resilience of the human spirit and the enduring power of culture. Despite the deliberate brutality of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the calculated attempts to erase their identities, and the immense challenges of cultural transmission across generations, the echoes of Biafra persist.

From the linguistic nuances in creole languages to the profound spiritual practices of Vodou and Kumina, from shared foodways to the symbolic power of Igbo Landing, the Igbo heritage is not merely a historical footnote; it is a living, breathing part of Caribbean identity. It highlights the often-overlooked specificity of African contributions to the formation of Caribbean societies and cultures.

Acknowledging this specific Igbo heritage is more than just an academic exercise. It is an act of historical justice, honoring the millions of Igbo ancestors who endured unimaginable suffering yet left an indelible mark on the lands they were forcibly brought to. It empowers descendants in the Caribbean with a deeper understanding of their roots and fosters a profound sense of connection to a vibrant ancestral homeland.

As researchers continue to uncover more evidence and as communities embark on journeys of self-discovery, the once “lost” Igbo diaspora is slowly but surely being found. This ongoing rediscovery is not just about the past; it is about strengthening identities, building bridges between continents, and celebrating the indomitable spirit of a people whose heritage refused to be extinguished by the tides of history. The whispers from the Bight of Biafra are growing louder, calling their descendants home.