The Igbo-Ukwu archaeological finds, located in modern-day Anambra State, Nigeria, represent one of the most transformative discoveries in West African history and art. Dating back to the 9th century AD, these sites revealed a highly sophisticated culture, long before the well-known metalworking traditions of Ife and Benin, which themselves flourished centuries later. The sheer technical virtuosity and aesthetic complexity of the copper and bronze objects unearthed not only established the region as an independent center for artistic innovation but also provided profound insights into the social structure, ritual practices, and long-distance trade networks of the ancient Igbo people. The entire corpus of Igbo-Ukwu art and material culture was primarily recovered from three adjacent, yet distinct, excavation sites: Igbo Isaiah, Igbo Richard, and Igbo Jonah.

The Accidental Discovery and Formal Excavation

The initial spark of discovery was accidental. In 1938, a local resident named Isaiah Anozie was digging a water cistern in his compound in the town of Igbo-Ukwu when he stumbled upon dozens of intricate bronze objects. Unaware of their immense archaeological significance, many of these initial finds were unfortunately dispersed. The importance of the discovery, however, eventually attracted the attention of the Nigerian colonial authorities, though formal investigation was delayed.

In 1959, the distinguished British archaeologist Thurstan Shaw was invited to conduct scientific excavations at the site. Shaw’s subsequent work, which included a second season in 1964, focused on the Anozie family’s property, leading to the meticulous study of the three sites named after the brothers who owned the compounds: Igbo Isaiah (where the original accidental finds occurred), Igbo Richard, and Igbo Jonah.

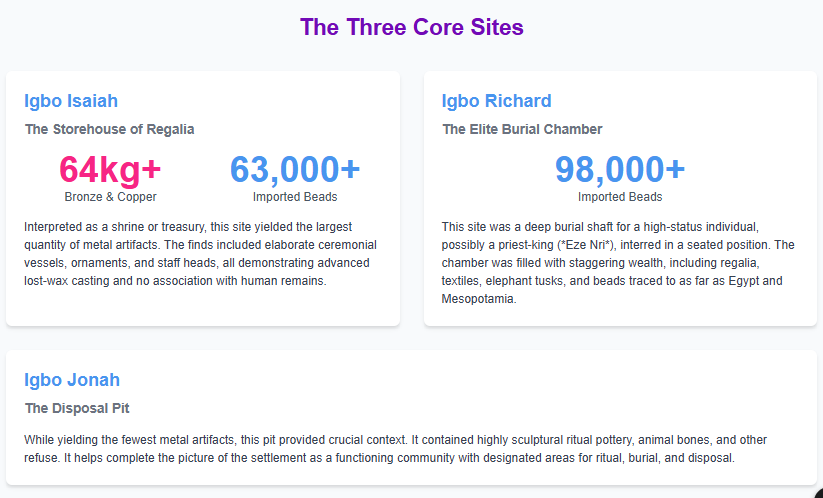

Site One: Igbo Isaiah (The Storehouse of Regalia)

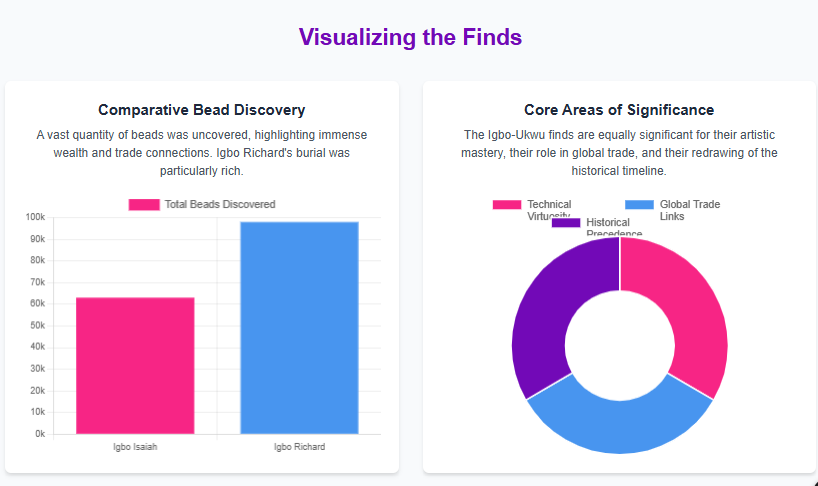

Igbo Isaiah, located at the core of the original 1938 find, was interpreted by Thurstan Shaw as a storehouse or shrine dedicated to the keeping of ritual vessels and regalia. This site yielded the largest quantity of copper and bronze material, weighing over 64 kilograms, alongside over 63,000 beads.

The artifacts recovered from Igbo Isaiah were not associated with human remains, but were found in a concentrated, deliberate deposition, suggesting they were carefully stored, perhaps within a shrine or treasury structure, that eventually collapsed or was ritually buried. The collection included some of the most famous pieces of Igbo-Ukwu art, such as the Roped Pot on a Stand , a masterpiece demonstrating the advanced cire perdue (lost-wax) casting technique. Many of the objects are elaborate ceremonial vessels, ornaments, and staff heads, often decorated with highly detailed surface textures mimicking ropework, insects, and naturalistic reliefs. The sheer volume and quality of these non-utilitarian, ceremonial objects point towards a stable, wealthy society governed by an elaborate, centralized religious or political system—possibly linked to the ancestral Nri Kingdom.

Site Two: Igbo Richard (The Elite Burial Chamber)

Situated about 30 meters southwest of Igbo Isaiah, the Igbo Richard site provided the most compelling evidence of social stratification and ritual activity. This site was an elaborate burial chamber, likely containing the remains of a highly important dignitary—perhaps a priest-king (Eze Nri). The burial itself was a deep shaft, where the deceased was interred in a seated posture upon a wooden stool (now disintegrated but evidenced by copper bosses).

The wealth of grave goods accompanying the individual was staggering, confirming their extraordinary status. The finds included:

- Regalia: A bronze leopard skull, a fan holder, ceremonial swords in copper-decorated scabbards, and various bronze ornaments.

- Trade Goods: An astonishing number of imported beads—over 98,000 glass and carnelian beads—many of which have been traced to sources as distant as the workshops of Fustat (Old Cairo) and Mesopotamia.

- Other Artifacts: Preserved fragments of ancient textiles, elephant tusks, and what appeared to be the remains of attendants sacrificed to accompany the dignitary into the afterlife.

Igbo Richard is crucial because it provides the social context for the artistic production. The concentration of wealth, the presence of foreign luxury goods, and the evidence of complex burial rites underline the existence of a hierarchical society capable of mobilizing significant labor and engaging in vast, trans-Saharan trade networks a millennium ago.

Site Three: Igbo Jonah (The Disposal Pit or Cache)

Igbo Jonah, the largest of the three excavated areas, yielded the smallest quantity of metal artifacts but provided crucial contextual clues, primarily in the form of pottery and refuse. This site was characterized by ancient pits, which were likely used as disposal caches.

While the exact nature of the pit remains debated—some suggest ritual disposal of unwanted sacred objects, while others view it as a general refuse area—the finds here were stylistically consistent with the other two sites. Noteworthy finds include highly sculptural ritual pottery, animal bones (mostly from wild species), and some bronze fragments. The pottery, in particular, showcases the distinctive aesthetic of the Igbo-Ukwu culture, featuring deep relief decorations and concentric patterns. Igbo Jonah helps complete the picture of the settlement, suggesting that these exceptional finds were part of a larger, functioning community with designated areas for ritual storage, elite burial, and material disposal.

Artistic and Historical Significance

The primary significance of the Igbo-Ukwu finds lies in the established chronology and the technical mastery demonstrated by the artists.

The 9th-Century Date: Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the sites date to around the 9th century AD, pre-dating the celebrated bronzes of Ife and Benin by several hundred years. This revelation was critical, as it decisively disproved the colonial-era speculation that such advanced artistic techniques must have been introduced by later European or Arab contact. Igbo-Ukwu proved that indigenous African cultures independently developed sophisticated bronze-casting traditions in the Lower Niger region.

Technical Virtuosity: The Igbo-Ukwu bronzes are renowned for their intricate details and complex execution of the lost-wax casting technique. Scholars like William Fagg described the style as having a “strange rococo, almost Fabergé-like virtuosity.” The artists excelled at producing thin-walled, highly detailed objects adorned with tiny figures, spirals, and threads, often combining multiple castings seamlessly—a technical feat that continues to astound metallurgists today. Evidence suggests the use of leaded bronze and copper, which were likely sourced locally, further emphasizing the resourcefulness and skill of the ancient smiths.

Implications for African Trade: The massive quantity of glass and carnelian beads, sourced from as far as the Middle East, confirms Igbo-Ukwu’s deep integration into a vast, intercontinental trade system. This trade was not necessarily direct but was likely facilitated through extensive interregional networks across the Sahara and down the Niger River, with the Igbo-Ukwu people trading valuable local goods—possibly ivory, spices, or slaves—for luxury items like beads and copper ingots.

In summary, the three sites of Igbo Isaiah, Igbo Richard, and Igbo Jonah collectively paint a vivid portrait of a highly developed, wealthy, and ritually complex society flourishing in West Africa during the early medieval period. They stand as a towering testament to the artistic genius and economic reach of the ancient Igbo civilization.

This draft is appropriate for a high school or introductory university level research paper. Let me know if you’d like to dive deeper into the specific metallurgical techniques used in the bronzes, or if you’d like to explore the connection between these finds and the subsequent Nri Kingdom history.