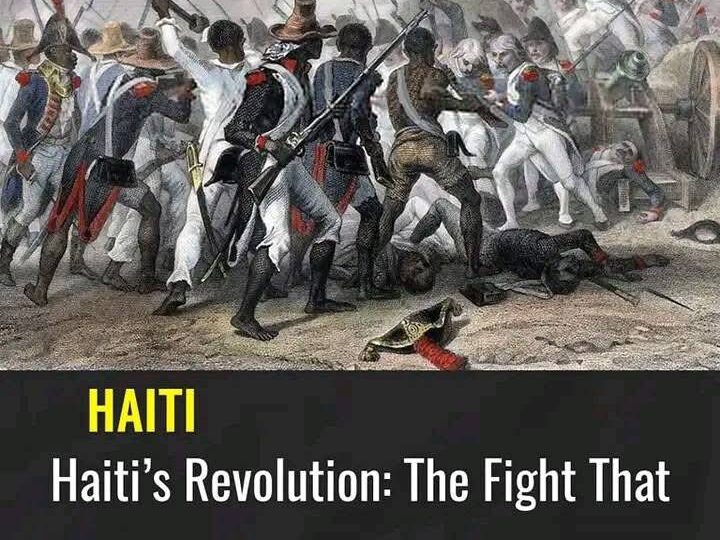

Haiti’s fight for independence is one of the most remarkable stories in history—a tale of resilience, courage, and the unyielding spirit of enslaved Africans who dared to defy one of the world’s most powerful empires.

In 1791, the enslaved people of Saint-Domingue, a French colony, rose up in a revolt that would eventually humiliate France and the West, proving that freedom could be won through sheer determination. Led by visionaries like Boukman Dutty, Toussaint Louverture, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the Haitian Revolution not only ended slavery in the colony but also established the first Black-led republic in the world on January 1, 1804.

This victory sent shockwaves through the Western world, challenging the foundations of colonialism and slavery. Yet, the cost was immense—Haiti was forced to pay a crippling indemnity to France, a burden that lingered for generations. Let’s dive into this incredible story, exploring how Haiti’s triumph reshaped history and why its legacy still resonates today.

SectioThe Spark of Revolution and Early Leader

The Haitian Revolution began in 1791, but its roots stretch back to the brutal realities of Saint-Domingue, France’s most profitable colony. By the late 18th century, the colony produced nearly 40% of the world’s sugar and 60% of its coffee, all on the backs of over 500,000 enslaved Africans who endured unimaginable cruelty (Geggus, 2002).

The French Revolution of 1789, with its ideals of liberty and equality, sparked hope among the enslaved, but the white planters refused to extend these rights to them. It was in this tense atmosphere that the revolution ignited.

On the night of August 14, 1791, a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman became the catalyst for rebellion. Boukman Dutty, a Muslim cleric turned Vodou priest, alongside Cécile Fatiman, led the gathering, inspiring the enslaved to rise against their oppressors.

Boukman’s speech, urging the people to “throw away the image of the white man’s god,” was a call to action (Wikipedia, Dutty Boukman, 2025). Within days, plantations were burning, and the revolt spread across the colony’s northern plains. Boukman was killed just months later, but his legacy lived on.

Enter Toussaint Louverture, a former slave who emerged as a brilliant military strategist. Born in 1743 on the Bréda plantation, Louverture had been manumitted before the revolution and owned property himself, giving him a unique perspective (Wikipedia, Toussaint Louverture, 2025).

He joined the revolt in 1791 as a lieutenant to Georges Biassou, quickly rising through the ranks. Louverture’s genius lay in his ability to navigate the complex political landscape of Saint-Domingue, forming alliances with the Spanish in Santo Domingo to gain resources, and later with the French after they abolished slavery in 1794.

Under his leadership, the rebels expelled British and Spanish forces, securing control of much of the colony. Louverture’s vision wasn’t just about ending slavery—he aimed to build a society where former slaves could thrive, a radical idea in a world built on racial hierarchy.

The Turning Point: Napoleon’s Betrayal and Dessalines’ Leadership

Just as it seemed Louverture was on the path to victory, Napoleon Bonaparte entered the scene, determined to restore French control—and slavery—in Saint-Domingue. In 1802, Napoleon sent his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, with a massive expeditionary force of over 30,000 troops to crush the rebellion.

This was a betrayal of the French Republic’s earlier abolition of slavery, a move that enraged Louverture and his followers. Despite fierce resistance, Louverture was captured through deception during a meeting with French officials in June 1802. He was deported to France, where he died in the cold, damp prison of Fort-de-Joux in April 1803, never seeing the fruits of his struggle (Wikipedia, Toussaint Louverture, 2025).

Louverture’s capture could have broken the revolution, but it instead fueled the resolve of his successor, Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Born into slavery in 1758, Dessalines was a fierce warrior with a no-compromise approach to freedom. He adopted a scorched-earth strategy, destroying French resources and making the colony uninhabitable for their troops. “Let them tremble when they approach our shores,” Dessalines declared, rallying his forces with a vision of total independence (Wikipedia, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, 2025).

The Haitian forces, now under Dessalines, used guerrilla tactics to devastating effect. They knew the terrain—swamps, mountains, and dense forests—better than the French, ambushing their columns and cutting off supply lines. Yellow fever, a deadly ally for the Haitians, decimated the French troops, who were unaccustomed to the tropical climate.

By late 1803, the French were on the brink of defeat. The decisive moment came at the Battle of Vertières on November 18, 1803, near Cap-Français. Dessalines, alongside leaders like Henri Christophe, led a final assault that broke the French defenses, forcing their surrender (Wikipedia, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, 2025). On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared Haiti’s independence, renaming the colony “Ayiti” after its indigenous Taíno name—a powerful symbol of reclaiming the land for its people.

The Aftermath and Global Impact

Haiti’s victory was a monumental achievement, but it came at a steep cost. In 1825, France, under King Charles X, demanded that Haiti pay an indemnity of 150 million francs to compensate former slaveholders for their “losses”—a sum equivalent to $560 million in 2022 dollars (Wikipedia, Haitian independence debt, 2025).

If invested, scholars estimate this could have been worth $115 billion today, a staggering burden for a young nation. Haiti was forced to take loans from French banks to pay this debt, plunging the country into economic hardship that lasted well into the 20th century. This “independence debt” was a cruel irony, punishing Haiti for its freedom and ensuring its economic subjugation to the West.

Globally, Haiti’s triumph sent shockwaves through the colonial world. It was the first successful slave revolt to establish an independent nation, a direct challenge to the racial hierarchies that underpinned slavery in the Americas. The revolution inspired other movements, from slave rebellions in the United States to independence struggles in Latin America.

Figures like Simón Bolívar drew inspiration from Haiti, reportedly receiving aid from Haitian leaders during his fight for South American independence (Geggus, 2002). Yet, the West responded with fear and isolation. The United States, a slaveholding nation at the time, refused to recognize Haiti’s independence until 1862, and European powers imposed trade embargoes, further isolating the new republic.

Haiti’s victory humiliated France and the West, exposing the fragility of their colonial systems. It proved that enslaved people could not only resist but win against a global superpower, a lesson that reverberated for centuries. Today, Haiti’s struggle is a reminder of the cost of freedom—and the resilience of those who fight for it.

Haiti’s fight for independence remains a beacon of hope and a stark reminder of the price of freedom. From the spark of revolt in 1791 to the triumph at Vertières in 1803, the Haitian people, led by Boukman, Louverture, and Dessalines, humiliated France and the West, proving that liberty could be won against all odds.

Yet, the indemnity imposed by France ensured Haiti’s victory was bittersweet, a burden that still impacts the nation today. Let’s honor Haiti’s legacy by learning from its resilience and advocating for justice in a world that still grapples with the legacies of colonialism. Want to explore more about Haiti’s incredible history? Check out afriker.com with the tag Haitian Revolution to dive deeper. For a scholarly perspective, visit this resource on Haiti’s independence debt with the tag independence debt on Wikipedia. Haiti’s story is one we should never forget.