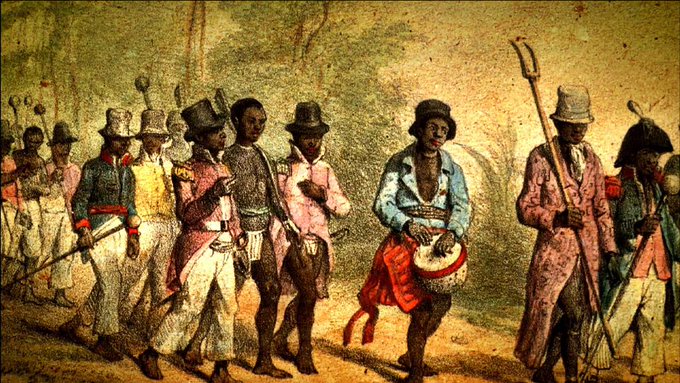

In many parts of Africa, when the skies withheld rain, people did not rush to laboratories or consult scientific instruments. Instead, they turned to the heartbeat of the land—the drum. The rhythmic thumping of carved wood and stretched hide reverberated through the air, sending a plea to the heavens. It was not merely music. It was prayer. It was protest. It was power.

But then came the colonizers.

They arrived with their ships, flags, and foreign tongues, dragging along with them a toxic concoction of superiority and violence masked as civilization. And where drums once spoke to the ancestors and skies, cloud seeding was introduced—a chemical coercion of nature, often hailed as innovation. The European mind called it “progress,” but to many African eyes, it looked like a brutal replacement of the sacred with the synthetic.

The Drum as a Spiritual Portal

In traditional African societies, the drum was never just an instrument. It was a voice. It could cry. It could command. It could console. The drum communicated across distances—announcing births, deaths, war, harvests, and rain-making ceremonies. Its language was understood not just by humans, but by spirits and deities. It summoned higher powers. It vibrated in harmony with the ancestors.

Now, that sacred role has been diminished. In many regions, drums have been reduced to mere cultural tokens—objects for entertainment rather than instruments of reverence. They are brought out for European tourists eager for “authentic African experiences,” but only if such experiences are conveniently packaged between 2 and 4 PM, right after the wildlife safari and just before dinner. The drum is no longer allowed to cry to the heavens. It is asked to smile for the camera.

The Rise of the Piano and the Erosion of Identity

Today, in a continent still reeling from the tremors of colonialism, the European standard of civilization continues to hover like an invisible hand shaping choices, aspirations, and even spirituality. It is in this context that we find a paradox: Africans who have managed to climb the shaky ladder of economic privilege often feel compelled to adopt symbols of Western sophistication—symbols like the piano.

A beautiful object, no doubt. Designed by Bartolomeo Cristofori in the 1700s, the piano is a marvel of craftsmanship and musical potential. But for the African steeped in a history of dispossession and spiritual disconnection, one must ask: what is this instrument doing in your living room?

Who are you calling with those ivory keys?

Which ancestor will turn their ear to the tune of Mozart echoing through your colonial bungalow? Does the spirit of your grandmother understand Chopin? Will the rains fall if you play Beethoven?

These are rhetorical questions, of course. But they underline a painful truth: the symbols of our spirituality are being replaced, one polished piano at a time. We are taught to revere the European form of expression, while our own are considered primitive. Barbaric, even.

To beat the drum in your own house may raise eyebrows. “It’s too loud,” they say. “Too tribal.” But a grand piano? That’s elegant. That’s cultured.

This is how colonialism wins—not just through political conquest, but through psychological warfare. Through a slow and steady reprogramming of what is considered sacred, acceptable, and aspirational.

The Spiritual Cost of Assimilation

The conversation isn’t about rejecting all Western innovations. It’s not a simplistic binary of drums versus pianos, or tradition versus modernity. It’s about memory. It’s about spiritual grounding. It’s about questioning why, over time, we were made to believe that what is ours must be hidden, and what is theirs must be displayed.

In urban African homes today, children learn to play classical European music before they are taught the drum rhythms of their forebears. Schools prioritize Shakespeare, but rarely delve into the oral epics of the Griots. Our tongues twist easily around French, English, and Portuguese, but stumble over our own mother languages.

And with every lost drumbeat, a spiritual portal quietly closes.

We must ask ourselves: what are we becoming? In our eagerness to “progress,” are we not merely dressing up in the very garments that once choked us? The erasure of the drum from our homes is not an accident. It is a symptom of something deeper: a disconnection from the divine essence of who we are.

Reclaiming the Drum, Reclaiming the Spirit

To reclaim the drum is to reclaim memory. To bring back rhythm into our homes is to restore a lost dialogue between the living and the spiritual. Let us not wait for tourists to validate our culture. Let us not wait for museums to showcase our sacred. Let us make room again for our own frequencies.

The drum is not outdated. The spirit it summons is not irrelevant. If anything, in an age where anxiety, rootlessness, and cultural confusion plague so many, it is more necessary than ever.

So no, it is not barbaric to have a drum in your house. It is not uncivilized to beat it. What is truly uncivilized is forgetting who you are because someone else convinced you their way is better.

Innovation is not a one-way road to the West. Let the rains fall again, not from chemically forced clouds, but from the heartbeat of a people who remember their power. Let the drum speak once more—not to tourists, but to the ancestors.