Colorism—the preference for lighter skin tones—has been a painful issue in many modern societies, but what about in ancient Kemet (Egypt)? Today, we often project our biases onto the past, assuming that ancient civilizations shared our struggles with skin tone discrimination. But the evidence tells a different story.

The Know Thyself Institute argues that ancient Kemet celebrated all phenotypes, from the jet-black skin of Nubians to the high yellow tones of Ethiopian Highlanders, with no trace of colorism (Know Thyself Institute, 2025). Imagine a society where diversity was a source of pride, not prejudice—a stark contrast to today’s world.

This article dives into the historical evidence of phenotypical diversity in the Nile Valley, explores how Kemet’s culture embraced all skin tones, and reflects on what this means for combating colorism today. Let’s travel back to a time when the Nile Valley showed us what true unity looks like, challenging us to rethink our modern assumptions about race and identity.

Evidence Against Colorism in Ancient Kemet

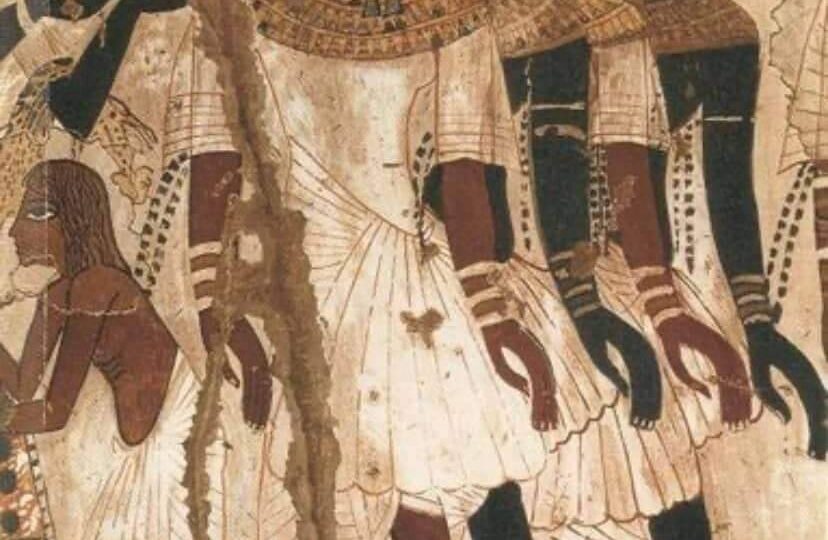

Ancient Kemet, thriving along the Nile from 3100 BCE, was a society of remarkable diversity. Archaeological and artistic evidence shows that the Kemites didn’t practice colorism—they celebrated it. Wall paintings in tombs, like those in the Valley of the Kings, depict individuals with a range of skin tones: jet black, reddish-brown, high yellow, and everything in between. These artworks, dating back to the Middle Kingdom (2000 BCE), show people of different phenotypes working, worshipping, and celebrating together, with no hierarchy based on skin tone (Kemet Expert, 2025).

This diversity reflects the Nile Valley’s role as a cultural crossroads. Nubians, often depicted with darker complexions, were frequent allies and traders with Egypt, as seen in the A-Group culture’s influence on pre-dynastic Egypt (Michinori, 2000). The Horn of Africa’s high yellow populations and the Sahel’s deep brown tones were also represented, often in scenes of unity. For example, the rhyton from the 18th Dynasty features Africans of various shades, suggesting that diversity was a point of pride, not division (Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, 2025).

Textual evidence supports this view. The “Instructions of Ptahhotep,” a Middle Kingdom text, emphasizes Ma’at—harmony and balance—as a guiding principle, with no mention of skin tone as a marker of worth. Even in royal depictions, pharaohs like Taharqa, a Nubian ruler of the 25th Dynasty, were celebrated for their leadership, not judged by their darker complexion. This absence of colorism is striking, especially when compared to later societies where skin tone became a source of discrimination. The Kemites’ focus was on unity, a value that allowed their diverse society to thrive.

Artistic Depictions of Diversity in Kemet

Art in ancient Kemet wasn’t just decoration—it was a reflection of society’s values. The Kemites used color symbolically, but not to discriminate. Men were often painted reddish-brown to symbolize strength, while women were depicted in lighter yellow tones to represent fertility—but these were artistic conventions, not judgments of worth. More telling are the depictions of diverse phenotypes in everyday scenes. In the tomb of Rekhmire, a vizier under Thutmose III, Nubians with jet-black skin are shown bringing tribute alongside lighter-skinned Egyptians, all treated with equal respect (Nile Valley Collective, 2025).

Sculptures and reliefs further highlight this diversity. The famous “Seated Scribe” statue, with its realistic features, could represent any number of Nile Valley phenotypes, from the reddish-brown Bishari to the high yellow Ethiopian Highlanders. Meanwhile, Nubian pharaohs like Taharqa were immortalized in statues that emphasized their distinct features—broad noses, full lips—without any hint of inferiority. This wasn’t tokenism; it was a genuine celebration of the Nile Valley’s people.

Mythology also played a role. Deities like Osiris, often depicted with dark skin, and Isis, shown in lighter tones, symbolized the balance of opposites, not a hierarchy. The Kemites’ art wasn’t about erasing differences—it was about embracing them as part of a harmonious whole. This is a far cry from modern colorism, where lighter skin is often prized over darker tones. In Kemet, diversity was woven into the fabric of society, a testament to the Nile Valley’s interconnectedness with Nubia, the Sahel, and the Horn of Africa.

This artistic legacy challenges us to rethink our assumptions. If a civilization as advanced as Kemet could celebrate all phenotypes, why can’t we? Their art isn’t just beautiful—it’s a lesson in unity, showing us what’s possible when we value diversity over division.

Combating Modern Colorism with Lessons from Kemet

The absence of colorism in ancient Kemet offers a powerful lesson for today’s world, where skin tone discrimination remains a pervasive issue. In many African and diasporic communities, lighter skin is often seen as more desirable, a legacy of colonialism and systemic racism. But Kemet shows us a different way. By celebrating all phenotypes, from the onyx black of Nubians to the citrine yellow of the Khoisan, the Kemites built a society where diversity was a strength, not a source of conflict.

This history can inspire modern anti-colorism movements. Imagine if we taught children about Kemet’s values, showing them that ancient Africans valued all shades equally. Platforms like afriker.com with the tag colorism are doing just that, sharing stories of African unity to challenge modern biases. By rooting our efforts in history, we can show that colorism isn’t natural—it’s a construct we can dismantle.

Kemet’s example also encourages us to celebrate diversity in our own lives. Whether we’re in Lagos, Harlem, or London, we can honor our varied phenotypes as a reflection of our shared heritage. This isn’t just about self-esteem—it’s about unity. The Nile Valley’s history of collaboration, where diverse peoples worked together to build a great civilization, can inspire us to bridge divides in our own communities.

Scholars at the Nile Valley Collective are advocating for this approach, pushing for educational programs that highlight Kemet’s inclusive values (Nile Valley Collective, 2025). By learning from the past, we can create a future where colorism is a relic, not a reality. Let’s take Kemet’s lesson to heart, celebrating all shades as part of Africa’s beautiful tapestry.

Ancient Kemet’s rejection of colorism is a powerful reminder that diversity can be a source of strength, not division. From their art to their values, the Kemites celebrated all phenotypes, building a civilization that thrived on unity. Today, this history challenges us to combat colorism, embrace our diversity, and work together as our ancestors did. Let’s honor Kemet’s legacy by creating a world where all shades are celebrated, whether we’re in Africa or the diaspora. Want to learn more about Kemet’s inclusive culture? Check out afriker.com with the tag colorism to dive deeper. For a scholarly perspective, explore this resource on Nile Valley cultures with the tag Nile Valley by the Nile Valley Collective. Together, we can keep Kemet’s lesson alive, building a future where diversity is our greatest asset.