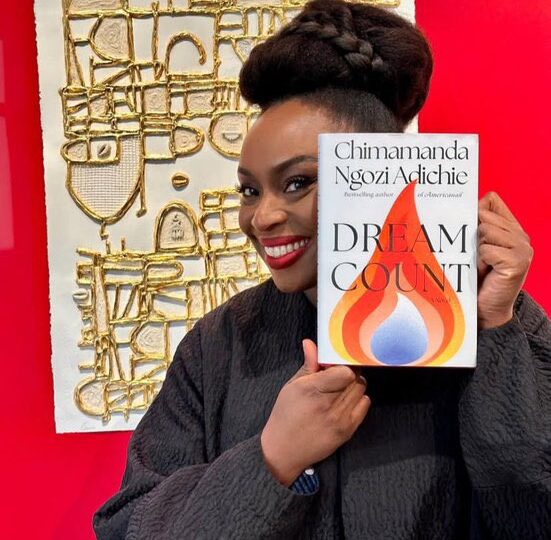

It has been over a decade since Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie last gifted the world a novel. After Americanah (2013), which deeply altered the literary landscape with its bold portrayal of identity, migration, and modern Black womanhood, Adichie became something of a cultural oracle — an author whose voice transcended pages and became embedded in speeches, anthologies, TED talks, and feminist thought.

But a novel is a different kind of act. A novel is slow; it requires emotional excavation, the kind that can’t be done on a stage or within the span of an interview. Dream Count, published in 2025, is a return to that space. It is an aching, slow-burning, sometimes brutal, always tender exploration of the lives of four women. It is also, perhaps most profoundly, a return to interiority — not just Adichie’s, but ours too.

The Premise: Four Women, One World Split in Fragments

At the heart of Dream Count is a simple but universal premise: what does it mean to be seen — truly seen — in a world that is constantly shifting beneath your feet?

The novel follows Chiamaka (Chia), a Nigerian travel writer stranded in the United States at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. What begins as an external dislocation turns into a deeper spiritual one. Through her, we are introduced to a constellation of other women:

- Zikora, her best friend and a high-achieving lawyer, who must confront betrayal from the man she trusted most.

- Omelogor, her cousin, a former Lagos banker now a disillusioned graduate student in Baltimore.

- Kadiatou, her Guinean housekeeper, whose life exists at the periphery of privilege but is brimming with untold struggle and wisdom.

These women form the emotional ecosystem of Dream Count. Their stories — layered, overlapping, contradictory — reveal what it means to carry the weight of expectation, history, love, and grief.

Time and Stillness: A Pandemic as Mirror

Set during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dream Count is not a “pandemic novel” in the traditional sense. The virus is not the protagonist. Instead, it is a backdrop that slows everything down. In that stillness, what has been ignored or avoided comes into sharper focus.

Chia, the travel writer, is literally grounded — unable to move, forced to live with herself and her past. Her long-distance relationship collapses. Her identity as a wanderer becomes useless. She is, for the first time, not telling a story but living one that has no neat ending.

Zikora is alone in a plush D.C. apartment, raising a child by herself after her partner leaves. Adichie does not dramatize her pain — she lets it simmer. We feel Zikora’s frustration, her desire for connection, and her refusal to be pitied.

Through Kadiatou, the novel confronts class in a way that is both biting and deeply empathetic. Kadiatou is invisible in the lives of the women she works for, yet she sees everything. Her dignity, built on her silence, begins to crack. It is one of the most searing portrayals of domestic labor in African literature.

Women and the Emotional Economy of Love

One of the most brilliant undercurrents of Dream Count is how it interrogates love — not the cinematic kind, but the kind women are often expected to perform, preserve, and perfect.

Adichie does not offer tidy conclusions. Chia is in love with a man who sees her as “almost enough.” Zikora loved a man who admired her ambition but could not handle her emotional needs. Omelogor, who once had dreams of being a writer, now questions whether love is something she has been conditioned to long for.

There is no fairy tale here. There is, instead, a realism so precise it sometimes hurts.

“We teach girls to love as an act of duty,” Chia reflects. “But what if love is a choice, every single day, not a currency we earn through suffering?”

Adichie writes women the way women often experience themselves but rarely see in fiction: whole, broken, selfish, generous, conflicted — but always human.

Friendship as Lifeline and Fracture

In Dream Count, romantic relationships fail, but friendships become sacred. Chia and Zikora’s bond is both a source of comfort and tension. They are not perfect friends. They hurt each other. But they keep coming back, not because they are obligated, but because they understand each other in ways no one else does.

Friendship is where the novel’s most profound conversations occur: about motherhood, race, loneliness, ambition. The dialogue — sometimes sharp, sometimes unbearably honest — reads less like fiction and more like listening to women talk when no one is watching.

Kadiatou, too, becomes a mirror to Chia. Their bond is not symmetrical. But it is transformative. In one unforgettable scene, Kadiatou tells Chia:

“I clean your house, but you live in mine — my memories, my loss. You just haven’t seen them.”

That line stays with you.

The Diaspora and the Dream That Counts

For readers familiar with Americanah, Dream Count may feel like an echo — but a quieter, more mature one. The novel is not concerned with dramatic “immigrant success stories” or the performance of identity. Instead, it captures the erosion of idealism. The American dream is no longer golden — it is grey, sterile, uncertain.

Omelogor, once a high-flying Lagos banker, now sits in a shared apartment wondering why her life in the U.S. feels smaller than the one she left. Zikora fights for respect in corporate boardrooms but is made to prove her worth twice as hard. Kadiatou works so her children back home can dream freely — a sacrifice rarely honored.

Adichie writes the diaspora with compassion, not celebration. It is a place of exile and reinvention, but also of erasure.

Language, Craft, and the Quiet Brilliance

Stylistically, Dream Count is luminous. Adichie’s prose is restrained but devastating. She is a master of dialogue — not just in what characters say, but in what they choose not to.

The novel’s structure — alternating between the voices of the four women — could feel disjointed in less skilled hands. But here, it feels organic. Each chapter bleeds into the next like conversations whispered across rooms.

The title, Dream Count, is never fully explained — and it doesn’t need to be. It suggests both the abundance and limitation of dreams. It is both hopeful and ironic. Each woman counts her dreams: some realized, some deferred, some stolen.

Loss and the Shadow of Adichie’s Grief

Since the death of her father and mother, Chimamanda Adichie has publicly shared her grief in essays and speeches. That sorrow echoes through this novel like background music.

Loss is everywhere in Dream Count. Not just death, but the quieter losses: of innocence, of belonging, of self. But what makes the novel bearable — even beautiful — is that it doesn’t dwell in despair.

These women survive. Not triumphantly. Not dramatically. But in the everyday acts of choosing themselves again and again.

Why Dream Count Matters

Dream Count is not a loud book. It doesn’t dazzle with plot twists or epic conclusions. But it is profound in the way only deeply honest fiction can be. It reminds us that women — particularly African women — contain multitudes. That stillness is as important as action. That dreaming, even when the world seems on fire, is an act of courage.

In a world that often demands simplicity, Adichie gives us complexity. She gives us women who are allowed to be everything at once.

Dream Count matters because it reflects us — our fears, our friendships, our silences, our resilience. It is Adichie’s most intimate novel yet, and perhaps her most necessary.